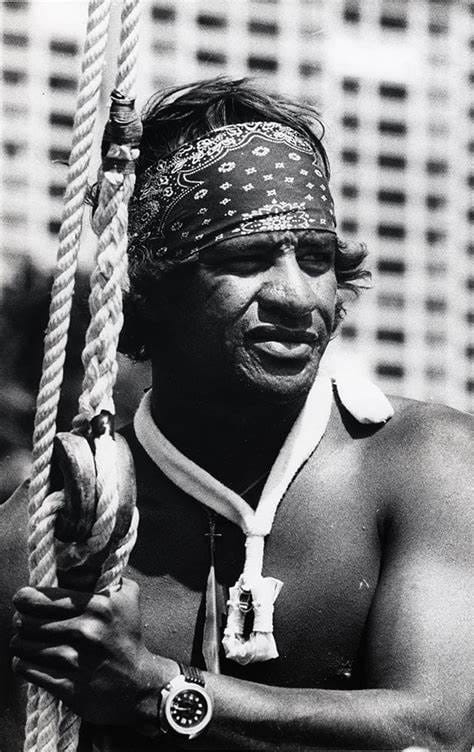

Eddie Would Go: The Life, Legacy, and Lasting Impact of Eddie Aikau

In the pantheon of ocean legends, few names carry the same gravity as Eddie Aikau. More than a surfer, more than a lifeguard, Eddie was a symbol of bravery, spirit, and selflessness. His legacy transcends wave size or lifeguard statistics—it lives in the soul of modern Hawaiian surfing and in a motto, that’s become a cultural mantra: “Eddie Would Go.”

The Early Life: A Son of Hawai‘i

Edward Ryon Makuahanai Aikau was born on May 4, 1946, in Kahului, Maui, the third of six children in a tight-knit Hawaiian family. The Aikaus eventually moved to Oʻahu, where the family lived near the cliffs of Maunalua Bay before settling in the working-class community of Lāie. His father, Solomon Aikau, was a deeply spiritual man who played traditional Hawaiian music and worked hard to provide for his family. The values of ohana (family), aloha (love), and kuleana (responsibility) were central to Eddie's upbringing.

Growing up in Hawai‘i in the 1950s and 60s meant surfing wasn’t just recreation—it was culture. It was identity. The ocean was a second home to Eddie, who dropped out of school early and took a job at the Dole pineapple cannery in order to afford his first big board. His dedication was relentless. He surfed before and after long shifts at the cannery, constantly refining his technique and developing a relationship with the ocean that went beyond sport—it was spiritual.

Waimea and the Rise of Big-Wave Surfing

In the late 1960s, Aikau began surfing Waimea Bay, the North Shore break famous for towering, bone-crushing winter swells. At the time, few dared to enter the water when the surf topped 20 feet. Eddie not only went—he charged, carving down walls of water with a grace and courage that stunned the international surfing community.

Waimea Bay had long been a sacred and feared site, where the ocean showed its full fury during winter swells. When the surf reached epic proportions, most would stay on the sand. Not Eddie. His style was bold yet calculated, drawing admiration from locals and visiting surfers alike. His presence in the lineup was magnetic—he inspired others to test their own limits.

By the early 1970s, Eddie had established himself as a pioneer of big-wave surfing. He became known not only for his physical prowess but for his deep respect for the kai (sea). In 1977, he won the Duke Kahanamoku Invitational, the most prestigious surf contest of the era. His win was a proud moment for Native Hawaiians, who often saw their own cultural contributions erased or sidelined by the growing commercialization of the surf industry.

First Lifeguard at Waimea Bay

In 1968, Eddie became the first official lifeguard at Waimea Bay, hired by the City and County of Honolulu. This was not a symbolic position—Waimea is one of the most dangerous beaches in the world. Over his nine years as a lifeguard, Eddie saved more than 500 people, often paddling into dangerous surf that other lifeguards would avoid.

Working without jet skis or modern rescue equipment, Eddie relied on his board, his body, and his skill. He built a deep trust with beachgoers and surfers alike, known for never hesitating in the face of risk. His commitment was total. Whether it was a lost tourist or a fellow surfer, he never weighed the risk to himself when someone was in danger. His presence turned Waimea from a deadly beach into a safer one, despite the raw power of the waves.

The Hōkūle‘a and a Hero’s Final Voyage

In 1978, Aikau was selected to join the crew of the Hōkūle‘a, a traditional Polynesian double-hulled voyaging canoe making a historic trip from Hawai‘i to Tahiti—without modern instruments, using only the stars for navigation. It was part of a cultural renaissance, a reclaiming of Hawaiian identity and pride.

The Hōkūle‘a's voyage was central to the Hawaiian Renaissance, a movement in the 1970s that sought to revitalize native traditions, language, and pride. Eddie’s participation was both a personal honor and a public statement—Hawaiians were once again embracing their identity as seafaring navigators.

Tragedy struck on March 16, 1978, when the Hōkūle‘a capsized in stormy seas south of Molokaʻi. With no rescue in sight, Aikau paddled off alone on his surfboard toward Lānaʻi to get help. It was the last time anyone saw him alive.

A massive air-sea search was launched, but his body was never found. Eddie was 31 years old. His death left a void in the hearts of many but also etched his name into the mythology of the ocean.

“Eddie Would Go” – A Legacy Becomes a Movement

In the wake of Eddie’s disappearance, a phrase began to circulate quietly in surf culture: “Eddie would go.” It started among lifeguards and locals, a way of honoring his courage and conviction. Over the decades, it grew into a global symbol of integrity and fearlessness.

The phrase has transcended surfing. It’s used in classrooms, in business meetings, by firefighters and frontline workers. It captures the essence of stepping up when others hesitate. Eddie’s courage has become a compass for those seeking to live with purpose and bravery.

The Quiksilver in Memory of Eddie Aikau

In 1985, the Aikau family and the surf industry launched the Quiksilver in Memory of Eddie Aikau—an invitation-only big-wave surf contest held at Waimea Bay, only when conditions are perfect: waves must reach a minimum of 20 feet Hawaiian scale (approximately 40-foot faces). The contest has only run 10 times in 40 years, due to the rarity of such swells.

The contest is not merely about performance. It’s about character. Only surfers who embody the spirit of Eddie are invited, and the criteria go beyond ability. Heart, humility, and respect for the ocean are essential. When the event runs, the world watches—not just for the waves, but for what the day represents.

Cultural Impact: Surfing as Hawaiian Resistance

Eddie Aikau’s story also intersects with the broader history of cultural resistance in Hawai‘i. At a time when native Hawaiian traditions were suppressed and the islands increasingly commercialized, Eddie’s life symbolized a reclamation of pride, dignity, and heritage.

The Hōkūle‘a voyage wasn’t just a canoe trip—it was a statement of sovereignty. Eddie’s participation placed him among the ranks of modern Hawaiian heroes who have helped restore native identity through action and sacrifice. His surfing, lifeguarding, and cultural advocacy represented a form of passive resistance to the erosion of Hawaiian values.

Conclusion: Why Eddie Still Matters

More than 45 years after his disappearance, Eddie Aikau remains a towering figure in surfing and Hawaiian culture. His life was brief, but his impact was tidal. Surfers around the world draw strength from his legacy; Hawaiian youth learn his story as a model of aloha, courage, and purpose.

Eddie taught us that surfing is not about ego—it’s about connection: to the ocean, to each other, and to the values that make us whole. In the words of Clyde Aikau: “Eddie paddled out not to be a hero, but because someone needed help. That’s who he was.”

In a world increasingly driven by self-interest and fear, Eddie’s story reminds us of the power of selflessness, courage, and community. His legacy challenges us to embody those values in our own lives—to act with bravery when it matters most, to look out for others even at personal cost, and to live with integrity in all that we do.

We could all stand to be a little more like Eddie. When faced with adversity or moments that call for courage, remember: Eddie would go.