The Bobby Bonilla Story

The Joke That Pays

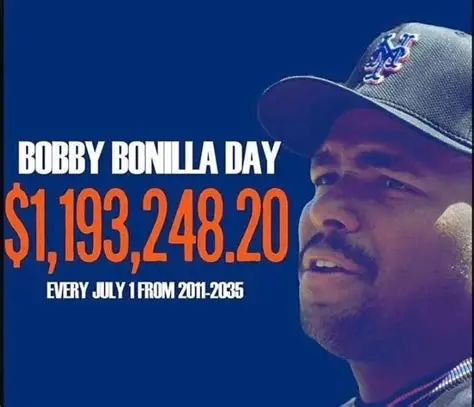

Every year on July 1, baseball fans across the country mark the occasion now affectionately known as Bobby Bonilla Day. It’s the day when the New York Mets, like clockwork, send a check for $1,193,248.20 to a player who hasn’t taken the field for them since 1999. To some, it’s a footnote in sports trivia. To others, it’s the gold standard of passive income.

Bonilla’s annual payday has become more than a quirky headline—it’s a modern fable. In an age where sports contracts balloon into the hundreds of millions and financial literacy is a rare asset, Bonilla’s story stands out. It’s a perfect confluence of shrewd negotiation, flawed assumptions, and the collapse of one of the most catastrophic financial schemes in American history.

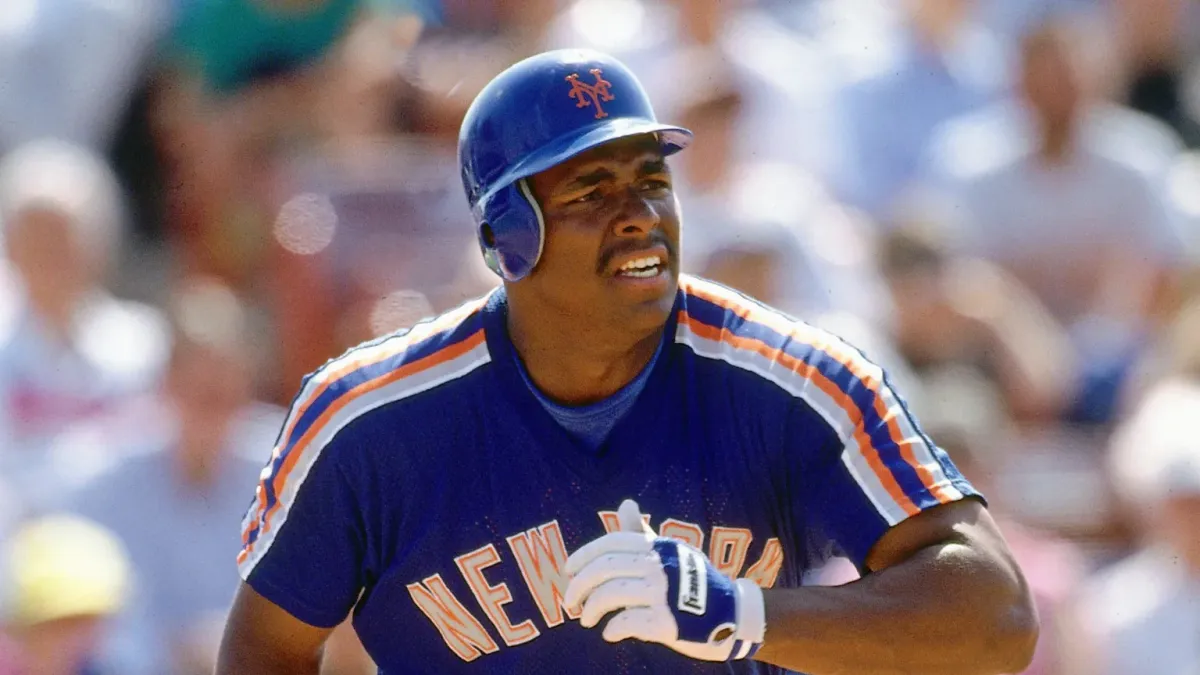

A Star in Decline

Bobby Bonilla’s career was nothing to scoff at. Over 16 seasons, he played for seven teams, earned six All-Star nods, won a World Series with the Florida Marlins in 1997, and finished with a respectable 287 home runs and 1,173 RBIs. But by the time he returned to the Mets in 1999, the spark had faded. He batted just .160 in 60 games and became a divisive figure in the locker room.

The Mets were ready to move on. They owed him $5.9 million for the 2000 season, but Bonilla wasn’t in their plans. Traditionally, they would have bought him out with a lump-sum payment. But Bonilla’s agent, the financially astute Dennis Gilbert, saw an opportunity far greater than an immediate payout.

The Contract: $5.9 Million Deferred at 8% Interest

Gilbert proposed something revolutionary: defer the $5.9 million until 2011 and then pay it out in annual installments of roughly $1.19 million through 2035. The catch? An 8% annual compound interest rate. The Mets, confident in their financial prospects, agreed.

This wasn't just a paycheck—it was a lesson in exponential growth. Over 25 years, that deferred amount would balloon to $29.8 million. Bonilla would essentially earn a lifetime annuity, all for walking away quietly from the team. It’s a deal that’s been dissected by economists, financial planners, and sports fans alike. (CBS Sports, 2023)

The Bernie Madoff Factor: A Mirage of Riches

So why would the Mets make such a seemingly lopsided deal? The answer lies with their financial advisor: Bernie Madoff. Mets owners Fred Wilpon and Saul Katz were heavily invested in Madoff’s fund, reportedly to the tune of $500 million. Madoff promised consistent double-digit returns, making 8% interest seem trivial.

The logic was simple: Let the money grow faster in Madoff’s fund, use the interest to pay Bonilla, and keep the principal intact. But in 2008, Madoff’s house of cards came crashing down. He was revealed to be orchestrating the largest Ponzi scheme in U.S. history, costing investors over $64 billion. The Mets were devastated financially—and still legally bound to pay Bonilla for decades. (ESPN, 2020)

Gilbert’s Masterstroke: Financial Literacy in Action

Dennis Gilbert wasn’t just thinking about 2000—he was thinking about Bonilla’s entire post-playing life. Having previously worked in the insurance industry, Gilbert understood annuities and compound growth. By ensuring Bonilla received a steady, guaranteed income stream, he provided his client with long-term financial security few athletes enjoy.

It was a revolutionary idea at the time. Many professional athletes end up in financial distress shortly after retiring, often due to poor financial planning or trusting the wrong advisors. Gilbert sidestepped all of that. Bonilla now earns more annually than many current MLB players—and he hasn't faced the risks of entrepreneurship or investment volatility. (MLB.com, 2020)

Deferred Payments: Not So Rare

While Bonilla’s deal gets the most attention, he’s far from the only player benefiting from deferred contracts. Teams often use them to create salary cap flexibility or spread costs over time. Some notable examples include:

- Ken Griffey Jr.: Still receiving $3.59 million annually from the Cincinnati Reds through 2024. (Spotrac)

- Chris Davis: Will collect $59 million from the Orioles through 2037 after retiring in 2021. (The Athletic)

- Bruce Sutter: Received $1.12 million annually from the Braves until 2021, despite retiring in 1988. (USA Today, 2023)

And in a modern example, Shohei Ohtani's record-setting contract with the Dodgers includes $68 million in deferred payments, demonstrating how widespread and normalized the practice has become.

Fan Reaction: From Embarrassment to Embrace

Initially, Mets fans viewed Bonilla Day as an embarrassment—a symbol of mismanagement and fiscal foolishness. But over the years, the narrative shifted. It became a beloved tradition, a yearly reminder of the absurdity of sports economics.

In 2021, new Mets owner Steve Cohen leaned into the joke. He tweeted: “Let’s make Bobby Bonilla Day a fun day. Buy everyone a hot dog and drink on me.” Fans appreciated the candor and humor, and the day turned into a celebration rather than a cringe-worthy reminder.

Now, each July 1st, social media lights up with memes, think pieces, and Bonilla trivia. What was once a mistake has been reclaimed as a moment of levity in a long baseball season.

The Meme Economy: Why Bonilla Day Lives On

Bonilla Day has evolved into a cultural artifact. It’s the subject of countless memes, financial planning podcasts, and even college business courses. It’s a rare sports story that transcends the game itself and becomes a commentary on wealth, planning, and institutional failure.

From ESPN’s coverage to CNBC's financial deep dives, the tale continues to gain relevance—especially in a post-COVID economy where inflation, student debt, and retirement planning dominate headlines. Bonilla’s seemingly silly payday has become a model of smart, stable, long-term wealth creation.

Conclusion: The Benchwarmer Who Won

The Mets entered the Bonilla deal believing they were buying short-term relief. Instead, they committed to a long-term lesson in the risks of speculative finance and poor forecasting. Bonilla, on the other hand, transformed a career twilight into a financial renaissance.

Every July 1, as that check is cashed and Twitter lights up, one truth remains: Bobby Bonilla may not have been the greatest to play the game, but he played the financial game better than most.

Key Stats Summary

| Category | Figure |

|---|---|

| Original Buyout (2000) | $5.9 million |

| Annual Payout | $1,193,248.20 |

| Years Paid | 2011–2035 |

| Total Received | $29.8 million |

| Interest Rate | 8% |

| Bonilla’s Last MLB Game | October 7, 2001 |

| Age at Final Payment (2035) | 72 |